The Negative World is undeniable, whatever we call it

My First Things article on the three worlds of evangelicalism featured as a part of the context for a recent debate over the legacy of Tim Keller (see here, here, here, and here among others). In that dispute, some people critiqued my framework. One of their points of dispute is about the dating of what I labeled the “negative world.” I want to explain why their critique of my framework fails to persuade and lacks explanatory power.

To refresh, my framework posits that during the period of secularization post-1965, America has passed through three distinct phases or worlds in terms of how secular culture views Christianity:

- Positive World (Pre-1994). Christianity was viewed positively by society and Christian morality was still normative. To be seen as a religious person and one who exemplifies traditional Christian norms was a social positive. Christianity was a status enhancer. In some cases, failure to embrace Christian norms hurt you.

- Neutral World (1994-2014). Christianity is seen as a socially neutral attribute. It no longer had dominant status in society, but to be seen as a religious person was not a knock either. It was more like a personal affectation or hobby. Christian moral norms retained residual force.

- Negative World (2014-). In this world, being a Christian is now a social negative, especially in high status positions. Christianity in many ways is seen as undermining the social good. Christian morality is expressly repudiated.

Like all frameworks of this type – such as the division of history into ancient, medieval, and modern – my three worlds model is a simplification of very complex phenomena, and designed primarily for utilitarian purposes. Unlike with theological or scientific models, which are claims to objective truth, frameworks like these are tools to help us make sense of and navigate the world. There may be many frameworks to explain the same phenomenon, each of which is useful to some people but not others, or each of which illuminates different dimensions of the situation. I always encourage people to try out different frameworks or lenses on a problem to look at it from multiple angles. Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option is a related but different lens, for example.

So I wouldn’t expect my framework to be the last or only word about how to interpret today’s world when it comes to the relationship of the church and secular society. Indeed, robust critique and the development of alternative points of view are key to understanding and adapting to our age.

Unfortunately, the current round of critiques was not especially useful. The main critique leveled at my framework is that there’s nothing new about the negative world, and that American Christians have lived in a negative world for some time. Thus, what I labeled the neutral world either never existed, or happened much earlier than in my accounting. We see this view best expressed by David French:

There are so many things to say in response to this argument, but let’s begin with the premise that we’ve transitioned from a “neutral world” to a “negative world.” As someone who attended law school in the early 1990s and lived in deep blue America for most of this alleged “neutral” period, the premise seems flawed. The world didn’t feel “neutral” to me when I was shouted down in class, or when I was told by classmates to “die” for my pro-life views.

It is objectively true that there was once a positive world in the United States. This world was, specifically, positive towards Protestant Christianity. Up through the 1950s, the United States had a well-documented Protestant establishment. Even Catholics could be excluded from certain institutions on account of their religion, and the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 as the first Catholic president was controversial at the time. The establishment’s religion was predominantly liberal Protestantism, but it was Protestantism to be sure. The divisions of this era were not Christian vs. non- or anti-Christian, but primarily sectarian and ethnic.

If there was once a positive world, and everyone, including French, seems to believe that we’re now in at least something of a negative world, then at some point in time, if even for a brief moment, there must have been a neutral world. The question is when the transition from neutral to negative happened. The critics of my model do not provide a specific date, but from arguments such as French’s above, we see that it must have been prior to the early 1990s.

Is it really the case that the culture’s view of Christianity and its moral systems are still basically the same as they were three decades ago, and that there was no major cultural break around 2014? I would argue No. There is very strong evidence for such a cultural break.

There was clearly a set of major shifts in American culture around the year 2014, or, to put it more broadly, during President Obama’s second term. One of them is the so-called “Great Awokening.” The Center-left technocratic writer Matt Yglesias dated the Great Awokening to the Ferguson protests of 2014. A Google search reveals a number of other writers making similar arguments. One academic study noted, “Our results show that the frequency of words that denote specific prejudice types related to ethnicity, gender, sexual, and religious orientation has markedly increased within the 2010–2019 decade across most news media outlets. This phenomenon starts prior to, but appears to accelerate after, 2015.” The authors point out that this started prior to Trump’s election run in the 2016 cycle, so it can’t be pinned entirely on him.

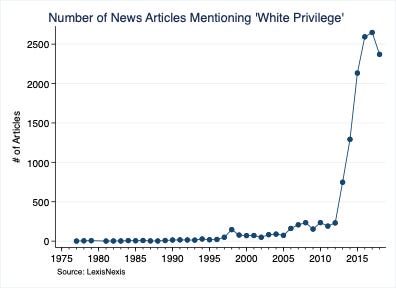

Zach Goldberg also did Lexis-Nexis searches for the appearance of a variety of terms related to the woke turn in the newspapers. They tend to show a quite stark acceleration in Obama’s second term, or even before. Here are some examples:

Clearly, something fundamentally changed in the discourse on race circa 2014, which has had a major influence on the key institutions of society.

Additionally, there was a major change in views towards homosexuality in this period. The Obergefell decision that legalized gay marriage was in 2015. This inaugurated a completely new legal regime in America around gender and sexuality issues that is still being elaborated. While the Obergefell decision itself was perhaps as much effect as cause, there was clearly a major and extremely rapid shift in public sentiment during this time period (albeit perhaps not as stark as with the Great Awokening).

In 2008, a majority of voters in California – yes, California – approved Proposition 8, a constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage. Also in 2008, Barack Obama campaigned for President as an opponent of gay marriage, specifically citing his Christian faith as a rationale. He was lying. He had in fact been on record as supporting gay marriage in the 1990s while a member of the Illinois legislature. But it’s notable that he felt compelled to lie about this issue, and even stress Christian bona fides in order to get elected. (Hillary Clinton also publicly opposed gay marriage at that time). By 2016, Donald Trump was personally holding up pride flags at rallies while running for President as a Republican. Today, the effort to prevent people who are male-to-female transgendered from competing in girls’ sports seems like a desperate rearguard action. This is quite a sea change in a short period of time.

There are other indications of a major cultural shift as well. The mere fact that someone like Donald Trump could get elected President in 2016 was a shocking development. Jonathan Haidt noted the he started seeing a change in student attitudes on campus around 2013. I’ve had people tell me about changes in the nature of the comedy world about that time (or a bit later) too. I’m sure there are other examples.

One reason my three worlds model resonates so much for people is that it takes account of this cultural break. I don’t think it’s necessary to interpret these shifts exactly as I did in demarcating a shift from a neutral to a negative world. They don’t even have to be put into a specifically religious context. But then how do you present and interpret them? The fact that some critics of my framework basically do not enunciate or grapple with these cultural shifts in a way congruent with their clear and substantive import helps explain why they are increasingly no longer viewed as guides to the culture.

The average person in America can sense that something has changed profoundly in the era since Obama won his second term. They might not be sure what it is, how to describe it, or what to do about it, but they know it’s there. Acting like it’s the same old negative world it ever was – or even, as French does, pointing out ways things have improved – is just not going to connect with people. It’s like continuing to describe our world in terms of concepts like relativism. It doesn’t speak to the mood of the culture or what the man on the street is sensing and or experiencing in his daily life.

I’ve been struck by Rod Dreher’s accounts of the growing number of emails he received from people relating unprecedented levels of hostility in their institutions, or who rejected his Benedict Option at first but are now convinced. I’ve also seen an uptick in resonance with my framework. Acceptance of the framework is growing because it speaks to the reality of the current cultural moment. By contrast, while the market for denialism and business as usual is still big, it’s shrinking by the day as people look for ideas that will actually help them figure out how to live in today’s cultural moment.

Image Credit: Pexels

This article was originally published at Aaron Renn’s Substack. Republished with permission.